Safety training for journalists in Central America

What do you need to know and be able to do in order to work as a journalist in violent countries? This is what media professionals from Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and Nicaragua learn in safety training courses. Free Press Unlimited invests in this kind of training around the world because safety and security — physical, digital and psychological — are basic preconditions for independent journalism.

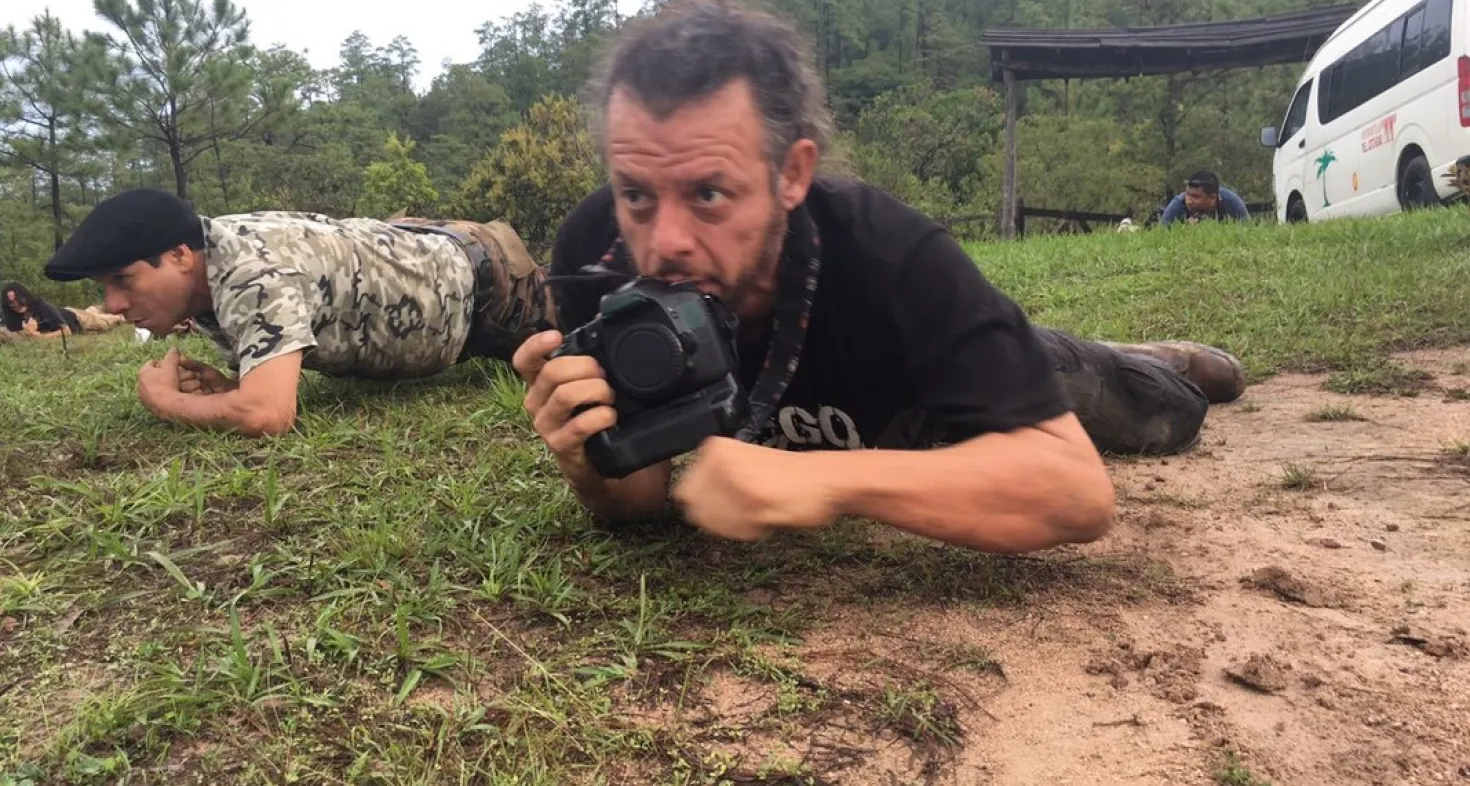

Diving for cover when bullets are flying, tackling a hostage situation and completing a long march through enemy territory carrying heavy equipment on your back. It sounds just like a military training programme, but in this case the weapon is a camera and the participants are journalists, not soldiers. They take these training courses in Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and Nicaragua, thanks in part to Free Press Unlimited. Such training is desperately needed in these countries. In Honduras and Guatemala alone, eight journalists were killed in violence in 2016.

Not just physical

The training prepares journalists for emergency situations and violence. In the countries where the training takes place, violence can be perpetrated by various different groups: militias, the government, but overwhelmingly by drug gangs. The training is not just about the physical side. It also deals with practical preparations: thinking about where you are going and how you can distinguish between safe and dangerous territory. It is important, too, to have the right equipment, such as GPS, maps and a medical kit. Last but not least, considerable attention is paid to being psychologically prepared. Before an assignment, journalists need to ask themselves whether they can cope with it. Training in mental resilience during emergency situations is essential.

Traumas

Enayda Argueta of Fundaciõn Latitudes: “That mental aspect is crucial. Don’t forget that the countries where we provide the training are ruled by violence, every day, year in year out. Some of the journalists taking part go out every night to record the trail of blood left by drug gangs and execution squads. They are almost without exception traumatised; they suffer from PTSD and receive threats. There is an extensive extortion industry operating in these countries, and drug gangs regularly infiltrate journalist organisations in an attempt to obtain information. So journalists in these countries leave their homes wondering what deadly risks they are running today to get the news.”

Learning the language and signs

In addition to the mental and physical aspects, the training also covers know-how. Drug gangs use a special language and they have their own codes and signs. If you don’t know them, you will immediately be in danger. If you want to enter an area controlled by a drug gang, you need to know who to contact. What should you do if you are approached via social media for information? How should you deal with online threats, or shifts in the power of the cartels? The training courses also aim to answer these kinds of questions.

Enayda: “In the past, you might have got away with calling out that you were from the press, and therefore unarmed and harmless. But that doesn’t work anymore these days. The gangs and militias no longer respect the press. That’s another reason why more training is needed. We see that the journalists clearly have more self-confidence after the training. They also prepare more for their hazardous work. We also believe they will deal better with emergency situations after this training, which could reduce the risks considerably. For example, journalists learn that they mustn’t abandon one another because you are more likely to make mistakes in an emergency situation if you’re alone than if you’re in a group.”

Breathe slowly

Take the case of Alex Cruz, a journalist in Guatemala. He wanted to expose how gangs are extorting money from minivan drivers. If they pay up, they are given a sticker that will let them drive on at the next roadblock. While he was filming this practice, he leaned out of his car window and some gang members spotted him. As he drove away, he was boxed in by two pickup trucks, a pistol was put to his head and everything was taken off him. Alex lived to tell the tale and admitted later that he could never have remained calm if he hadn’t taken the training course. Instead of panicking, he continued to breathe slowly, something he had practiced in the simulation of serious intimidation by armed instructors.

“Police militarisation also plays a role in journalists’ safety”, says Enayda, “for instance, riot control units are increasingly being given tanks. For journalists, it’s a question of keeping an eye on these all the time while they work, with 180-degree vision. We also learn to keep looking out for escape routes while we work.”

Aggressive themselves

It is not just about ensuring the safety of the participants in response to the threat of violence against them. Sometimes the journalists themselves use aggression when working. Reporters in El Salvador, for instance, have been involved in social protests and disturbances among football supporters at matches. Then the boundary between journalist and activist can sometimes become blurred: journalists fight their way through police cordons and adopt an aggressive style in interviews. This often goes hand in hand with the enormous drive that lets journalists work seven days a week under huge stress. The never-ending tension leads to extreme behaviour, sometimes without the journalist noticing. This is evident in how they approach sources and it affects the quality of the journalism. This aspect too is covered in the training courses.

The violent conditions in which journalists work in these countries often turn them into nervous loners. In the training sessions, they work on achieving more self-awareness, calm and a balance between work and private life. Together, all these aspects should make journalists safer and thereby help improve journalism.

Photo: Fundación Latitudes